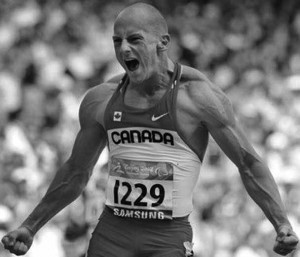

Determination puts Earle Connor at the top

Failure and defeat have never been part of his vocabulary

Angie Lang

Sports Editor

The moment Earle Connor started training again for the 100m and 200m sprint, the new goal was to find a balance between being an older athlete, owning a business and having a family so that he could be successful in every part of his life.

Connor has had his fair share of ups and downs, but his business ‘Simply for Life’, a weight loss and nutritional counseling clinic in Cochrane, Alta, is still going strong. Connor is nothing but smiles and cheerful emotions. We sit down on the large leather couches. In front of us on the coffee table are multiple sport magazines scattered and the television broadcasting a soft hymn of sports highlights on TSN.

Connor lost his left leg from the knee down when he was three months old after being born without a fibula. At nine months, he was fit for his first prosthetic and was walking at eleven months. His parents actively tried to make sure that their son was not treated differently.

Connor’s passion and determination to be the best is what sets him apart from other athletes. His constant need for improvement because of failure is what puts him at the top of his sport.

“It almost, I don’t want to say becomes addictive, but becomes a pattern where you know what you’re doing is working so you want to continue to do it and exploit it,” Connor said.

He was the kid who would scream and throw a tantrum after dinner if he couldn’t go and play catch in the backyard with his dad. Growing up it was never about having a missing left leg; it was about finding the next avenue of sports to exert his energy and competitiveness.

“Grade 1 through 4 , my mom taught on an Indian reserve, so for me getting to play hockey wasn’t about fitting in because I had a prosthetic leg, it was about fitting in because I was the only white kid,” Connor said.

From an early age, Connor’s veins flowed with the love of sports.

“I picked strategic [sports] that not only genetically I would be good at but also mentally that I wouldn’t fall too far behind. I had the mind set of what I could and shouldn’t do,” Connor said.

The first 19 years, Connor didn’t run track and field at all. His main passion was hockey. At age 15, he was the first disabled person drafted into the WHL, but he is the first to admit that he sucked.

“I made it to as far as my body would let me go,” said Connor. His next step was to find an outlet for his desire to keep participating in activities.

This helped Connor council other people with limitations in his current career as a health and fitness advisor at his business ‘Sports for Life’. He said that what sets him apart from all the other health clinics out there is that he doesn’t beat around the bush, he tells it to his clients straight.

“I know that people aren’t going to follow the plan all the time. I want an 80 to 20 per cent commitment. I know life happens and things come up,” said Connor.

The same passion that shines through Connor’s voice when he talks about helping his clients shines though when he begins speaking about his journey through competitive sprinting. He starts laughing when he talks about his first competition in San Diego in 1998.

“They had to think really long and hard about letting this random pasty white Canadian guy with glasses in to the race,” Connor said.

This was the beginning of Connor’s success. He won the 100-meter sprint, 200-meter sprint and the long jump.

“So here I was begging to get in to the race and then this random unknown guy from the middle of Saskatchewan shows up and takes home $45,000.”

Connor describes this as the point that got the ball rolling to where he is now.

Sydney, Australia marked a special time in Connor’s sprinting career in 2000. His goal when he first started training in 1996 was to make it to the 2000 Paralympics and at least make eighth. Connor’s drive to succeed led him to victory and he brought home gold in the men’s 100-meter.

Looking back, Connor said the proudest moment in his career came from a huge negative. From the time period between winning gold in Sydney to two weeks before leaving for the 2004 Paralympics in Athens, Greece. He was getting faster, breaking records, making new records and was the favorite going in to Athens.

Then his life came crashing down when he was diagnosed with a pre-cursor to testicular cancer.

At the age of 27, Connor said that he didn’t want anyone to know, he was embarrassed and the only person who knew about the surgical procedure to get one of his testes removed was his dad.

Connor glanced down at his left leg, nostalgia fills the air. Connor, who had been named the fastest one-legged sprinters in the world, reflects on one of the hardest times, not only in his career, but of his life.

“I didn’t declare my medicine, but I was given them by a normal doctor. Two weeks before going to Athens going over as the preferable favorite and my goal being to defend my 100-meter title, I get a knock on my door for a random drug test and I knew from the moment I let him in that there was going to be a problem,” Connor said.

But after a two year suspension Connor came back to add another gold medal to his collection in the 100-meter sprint at the 2008 Paralympics in Beijing. Even though he won the race with a 12.3 second time, it wasn’t good enough. He remembers thinking to himself, ‘this sucks.’

“I knew there was more in my body to give and the conditions just didn’t allow me to do that.” He arrived home and retired at the age of 32.

But after three and a half years of being retired, his passion to compete and the drive to win was reignited. He placed fourth at the 2012 Paralympics, the first time he had ever lost a race.

Connor is now in the process of training for the 2016 Paralympics in Rio. He plans to regain what he feels he lost in London in 2012. The fight for gold has never been more in sight then it is now.

Connor says he wouldn’t be pushing his body, if he didn’t think he was going to win. From the moment he crossed the finish line in San Diego more than 15 years ago, he knew it was something that he could do and he could win at.

He never felt like success ever came too quickly for him or was overwhelming.

“I knew that I had an opportunity to exploit whatever athletic pieces of gifts that were inside of me,” Connor said.

Connor recognize’s that he has a disability, but he never used it as an excuse. He has a strong drive that burns for being competitive, but he has never pushed himself to the point of failure.

Connor uses his passion for health and fitness and inspires others to take on the same view in life. Connor explained that if people want a quick fix for a couple of months to go on Jenny Craig or use diet pills but he is going to give them the tools they can use to help them maintain a healthy life forever.

“I don’t tell people crap. I give them comments and true critiques that will help them believe in themselves. It’s something that comes from the heart that people can tell is genuine,” said Connor.

Connor speaks passionately about one of his longer-term clients who came to him knowing that if she didn’t make a change in her diet, fitness and life that she was going to die.

“You’ll meet a million people who have a disability and a million people will say you can do anything anyone else can, well no you can’t. I’m sorry. If someone’s in a wheelchair they can’t walk, you do have it whether it’s a major or a minor limitation, it’s there. I just had to be smart with what I was doing,” Connor said.

Connor currently is training indoor during the winter and will begin running sprints outdoors in the summer. He hopes his hard work and determination will pay off in Rio De Janiero and he will come home with yet another Olympic gold medal to add to his collection.