Opinion: Believing “fake news” breaks down to user-error; learning media literacy in the age of confirmation and automation bias

by Lily Dupuis, Contributor

When I watched “Behind the Curve” back in 2020, the 2018 Netflix documentary about the growing community of flat-earth believers made me somewhat obsessed with media literacy.

The film started off as comical. My partner and I laughed as we ridiculed the people on screen, “how can people believe this?”, we joked. Yet the film’s unexpected message slowly crept its way into my brain, eventually making a home within my conscience.

The film identified the “flat earthers” as vulnerable members of society. It showcased how technology has created new gateways for conspiracy theorists to exist in echo chambers built from cognitive dissonance.

Identifying a misinformed populace as “vulnerable” is the message that stuck with me. It’s saddening that society is often quick to leave these individuals to their own devices, sequestering them within a sea infested by “fake news” via social exile.

But I get it; debunking someone else’s troubling ideologies sucks, especially when they’re not really interested in listening in the first place. It’s exhausting.

My point, however, is that we need to hold ourselves accountable for our own media consumption, and as digital citizens, we still need to help each other out. Developing media literacy skills is something all of us should care about, à la “teamwork makes the dream work,” or something like that.

“Fake news” is more than we think

Not only did that documentary spark something inside me, but also my interest around the topic of media literacy has become increasingly piqued throughout the course of my degree. As a journalism and digital media student, I feel a sense of responsibility and obligation to share all that I’ve learned on the subject of critically analyzing media.

It’s important to acknowledge my privilege when understanding that my access to education is largely responsible for providing me with the resources and opportunities to develop my own media literacy skills.

But what about those who aren’t in my position?

Truthfully, journalists and other media specialists have a duty to share our methodologies for proper media literacy with everyone else.

And yes, that means our grandparents, too.

I’d like to start by exploring “fake news” and how it exists now as a new media object in the digital age. It would be adverse for me to discuss media literacy without sharing some thoughts on how the technological revolution has evolved the ways we interact with news.

“Fake news” is essentially just a mixture of misinformation and disinformation.

First, let’s make sure we’re clear on the difference between misinformation and disinformation. The most important concept in order to differentiate between the two is intent.

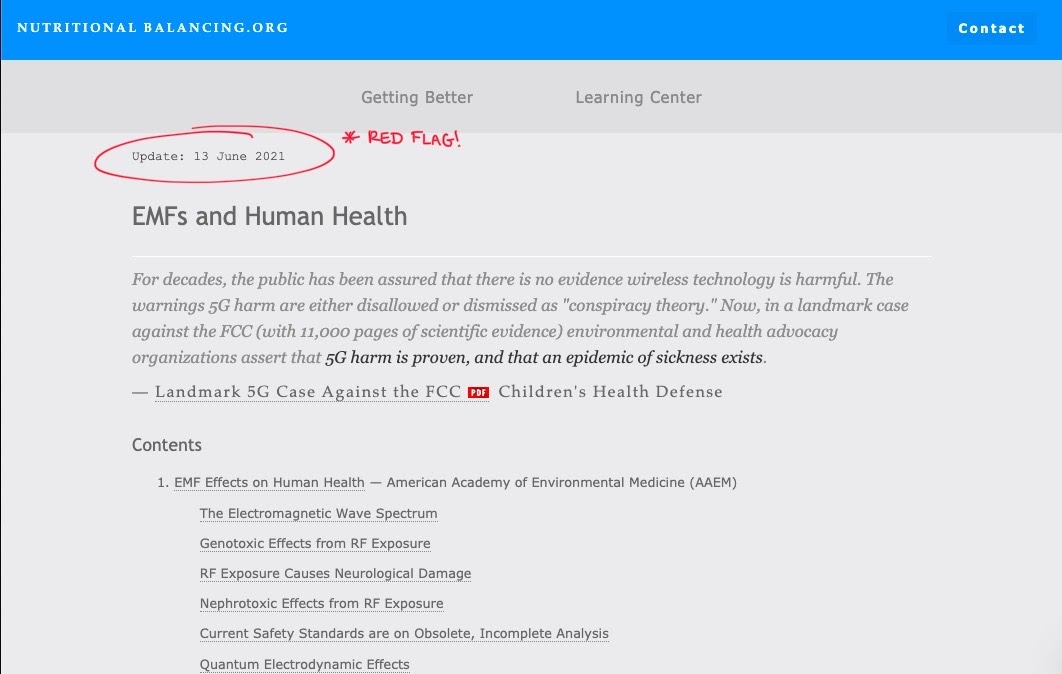

Misinformation is often unintentional, and it is typically a symptom of improper fact-checking or careless mistakes. It can also be identified in pseudoscience by using incomplete research to back up baseless claims. Misinformation still has harmful consequences, yet the intent behind the spread of misinformation is not conducted with the same malice as its counterpart. An example of misinformation when it comes to online quackery is this deceiving article that warns readers of the dangers of 5G. But please note that this is pseudoscience disguised as genuine scientific research.

Screenshot taken from the article on nutritionalbalancing.org’s website. Notice the update date on the article; these are red flags when we notice how they update whenever we visit the page to give the reader the illusion that the information is current.

In using this example, there are a few red flags I’d like to point out. Notice the website this is found on. The disclaimer at the bottom of Nutritional Balancing.org’s webpage states:

Nutritional Balancing.org is a free, non-commercial, public information resource. The information provided is for educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for the advice of a physician or other licensed health practitioner. The information provided is not intended to be used for diagnosis, treatment or prescription for any condition, physical or emotional, real or imagined. Statements contained herein have not been evaluated by the FDA.

In essence, it’s not their problem if you take what they say seriously.

Screenshot from nutrionalbalancing.org’s disclaimer page. I’ve highlighted some areas that should stand out to readers as problematic.

Next, pay close attention to the use of inflammatory language. Anything that aims to generate an emotional response is likely not trustworthy. Also, anything peer reviewed would not contain this type of emotional flair or grammatical mistakes.

Even that seemingly impressive reference list is anything but reliable. Take a look at the dates on this specifc article’s references, some of which going all the way back to 1965. (Luckily, scientific data on the topic has been updated since then.) This article even cherry picked bits of information from these sources, some of which don’t have much to do with their claims on 5G.

Also, please keep in mind that just because an author has “M.D.” in their title, doesn’t mean they’re right. Dropping fancy titles or organization names can also be a red flag. The article is also sanctioned by the American Academy of Environmental Medicine, which sounds very professional, but a quick Google search shows that it is listed as a “questionable organization.”

Noticing these misinforming red flags takes time, but once you see it, you’ll likely keep picking up on it.

Disinformation, on the other hand, is intentional.

It is entirely untrue, and it is used to deliberately mislead. Disseminating disinformation is a symptom of a more insidious agenda. At its best, it warps the facts, but at its worst, it manipulates the emotions of an audience to conjure up fear and irrationalism.

The most ridiculous examples of disinformation come from Donald Trump’s now disabled Twitter account.Interestingly, but not surprisingly, some of his most popular tweets contained blatant lies about the 2020 U.S. presidential election results. Sadly, this is a true testament to how powerful the effects of drinking the proverbial digital Kool-Aid can be.

Technology, algorithms, and biases

As a new media object in the scope of Lev Manovich’s theory, “fake news” manifests itself in various shapes and forms. It can look like conspiracy theories, pseudoscientific articles, lies from politicians or corporations on social media, etc., all of which are scattered throughout various websites and online locations, accessible to anyone with an internet connection.

In my mind, media literacy also means recognizing the interrelationship between technology’s increased efficiency and our capability for critical analysis.

Because the digital age has revolutionized the way we do the most mundane things, I have to wonder if it has also evolved our most basic cognitive functioning. Has consuming news media via technology changed the way we think?

Perhaps our desire to achieve the path of the least cognitive resistance has impaired our abilities to embrace cognitive resistance. This resistance, when it comes to media literacy, happens when we have to really dissect the message behind the content we consume.

This leads to a dependency that manifests an automation bias that potentially prevents us from critically engaging with media at all.

We have a predisposition to favour the machine, as we appreciate its propensity for making our lives easier. The user–i.e., us–is then so trusting of the system that misuse occurs when we don’t think twice about what it tells us.

For example, have you ever been using the map on your smartphone, and it directs you to the wrong place, but you mindlessly followed it anyways? That’s automation bias.

You trusted what the computer told you, and you probably did it without a second thought.

Algorithms only add fuel to this garbage fire.

Algorithms have fabricated filter bubbles, and the normalization of these echo chambers of devious disinformation are protected by capitalism.

The scope of our online presences are curated in line with the commodification of our personal data. This has even created an entirely new economic structure — i.e., the data economy — which is how we know the digital age is only going to continue to evolve the world around us.

Because of this, the very nature of fake news that brings the misinformation and disinformation we see online often confirms our already cemented ideologies.

Filter bubbles are a direct consequence of algorithms manipulating our ability for critical analysis. Unfortunately, as long as someone’s making money off of them, they’re here to stay, which highlights the need to strengthen our critical eye towards the media.

Sometimes we know that many of our belief systems are flawed or biased, sometimes we don’t, but ultimately it doesn’t matter, because it’s true to us, much like how Trump’s aforementioned most popular tweets were also some of the most inaccurate.

The Southern Poverty Law Center, a nonprofit organization dedicated to legal advocacy for civil rights, explained the dangers of algorithms and propaganda in a video about Dylann Roof. Roof is the American white supremacist responsible for the racially-motivated 2015 Charlestoon Church shooting that claimed the lives of nine African Americans.

The video proposes that Roof became trapped within a filter bubble of white supremacist propaganda after consistent exposure to it online via tailored search engine algorithms.

Fake news feeds confirmation bias, through and through. It reinforces what we already believe to be true, even if it isn’t.

Nothing in this universe is inherently “good” or “bad.” It is my belief that most things, especially technology, occupy a sort of grey area, and it is our relationships with them that determine whether or not they play a positive or negative role in our lives.

Simply put, we have to start questioning if our relationship with technology has altered our capacity for critical thinking.

Conspiracy theories and the need to know

With the web’s increasingly accessible databases of information, the spread of untruths is unregulated, underestimated, and terrifying.

It becomes an even greater cause for concern when considering conspiracy theories.

The pandemic has made me question if the appeal of conspiracies stems from a psychological place of humans being uncomfortable with the unknown; we’re always clinging to the comfort of finding an explanation.

In this 2020 Harvard Kennedy School of Communications study, researchers took a look at conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 pandemic.

Two groups were examined: those who claimed that the pandemic was “exaggerated,” and those who believed it to be part of some greater government agenda. The conspiracy theorists were, to my surprise, actually stretched out across a variety of political and sociodemographic factors.

So, maybe it’s not just about education. I can praise my education all I want, but that makes me no less aware of the biases that exist due to my own lived experiences and ideologies.

On that note, the study’s findings identified that there was a correlation between the belief of the aforementioned conspiracies and political or psychological motivations.

Equating media literacy skills with education seems reductive; it’s more than that. Hence why I’d like to emphasize the importance of user awareness.

This solidifies why discussing confirmation and automation biases is important when it comes to media literacy. The topic stretches further than just accessing proper education, and it presents itself as more of a personal dilemma

Is fact-checking the remedy?

Many would argue that fact-checking is a reactive approach, or “band-aid solution,” but that doesn’t actually address the fundamental issue: a need for proactive critical thinking.

The more I learn about this subject, the more I’m inclined to agree. If the fundamental issue is indeed a need for critical thinking in the first place, fact-checking and extensive research can only do so much. If reducing this to an education issue doesn’t address our engendered biases, what will sharing resources do?

Fortunately, this is not to say that I see zero value in the expansive encyclopedias of information, fact-checking resources, and quality journalism that exist online.

If we are able to recognize that technology and the internet have achieved some good, we must also be able to trust that truth exists in the media. New media objects can also help correct corrupted thinking patterns when we are consistently exposed to the same fact on a repetitive basis.

I’d implore all consumers of any media to welcome a healthy level of skepticism into their minds, but to also accept a fact when you see it. Maintaining balance is important, and this, I cannot emphasize enough.

So, don’t grab your tinfoil hat, but do grab your phone; just research it.

In the true spirit of trusting what you read online, I’ve linked some resources to fact-checking websites that can be bookmarked and saved for when you need them most. From a journalistic standpoint, these are ad hoc websites devoted to increasing media literacy in some way or another.

Media Literacy 101: Websites for fact checking, analyzing, and sourcing information

- Independent and nonpartisan website devoted to fact-checking and contextualized analysis

- Fast; Snopes is often the first to fact-check media claims

- Founded by researcher David Mikkelson (known for writing about/researching urban legends, rumours, internet claims, etc.), later joined by his wife, now owned by Snopes Media Group due to the platform’s growth

- Created by independent reporters from the Tampa Bay times, but now owned by the nonprofit Poynter Institute for media studies

- Run by independent editors and journalists, avoiding ever expressing any political values

- Uses the ever-accessible “Truth-O-Meter” to visualize the validity of claims in the news media

- *Has partnerships with Facebook and TikTok to slow the spread of misinformation/disinformation online (e.g., users see that certain posts are flagged when deemed inaccurate or misleading, read more about their methodologies here)

- Also runs PunditFact

- Nonpartisan and nonprofit; self-proclaimed “consumer advocate”

- Monitors factual accuracy of claims from U.S. politicians

- Project created by the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania (UPENN)

- Nonpartisan website

- Focussed on giving users information on “eRumours;” frequently addresses fake news from social media

- Founded by journalist Rich Buhler and run by journalists and other career media professionals

- Nonpartisan, nonprofit, and independent research group

- Monitors and tracks financial affairs of U.S. politicians

- Run by the Center for Responsive Politics

- Nonprofit, independent newsroom

- Produces investigative journalism handling various matters of public interest, often in the interest of holding powerful individuals and institutions to account

- Pulitzer Prize-winning website

- Nonpartisan and nonprofit foundation

- Advocates for open government and uses various approaches to the collection and publication of information

- Nonprofit, web-based research center

- Self-described as left-leaning due to monitoring and correcting specifically conservative misinformation and disinformation

- Web-based network of websites and other media dedicated specifically to investigating “quackery-related information”

- Developed by Stephen Barrett, M.D., but maintained by the Center for Inquiry (CFI), which is a nonprofit dedicated to mitigating pseudoscientific beliefs

Fact Checker from the Washington Post

- Relatively left-centre biased website due to fact-checking conservative political claims more often than liberal ones, but the fact checks are still responsible and ethically sourced

- Independent website that rates the bias, accuracy, and credibility of various media sources

- Outlines the methodology for how bias is determined

- Developed by Dave Van Zandt and run by himself and a network of volunteers

- Website that exposes people to information/discord from all political perspectives

- Run by a team of various people, all with rankings of their political biases listed on their website

- Curates stories/headlines to offer readers comparisons on how bias influences right, center, and left leaning media coverage

The time for media literacy is now

All in all, while I recognize that cataloguing resources doesn’t address the fundamental issues of media literacy, I do believe that they can at least help.

I encourage all digital citizens to be wary of the content we consume. Take the accountability into your own hands, and explore all the ways in which you may be victim to confirmation and automation biases.

Consequently, be mindful of those who surround you who may be stuck in filter bubbles. So often it is our loved ones (perhaps older relatives) that need our help. If the emotional toll isn’t too costly, giving people the resources to develop their media literacy skills can be a really beautiful thing.

And finally, this is an opinion piece. Take everything you read online with a grain of salt, I guess.

If you’d like to further your research on this topic, take a look at some of these resources:

- Toronto Public Library, “How to Spot Fake News”

- Carleton University, “Fake News and Content Evaluation”

- X University, “Fake News”

- Walden University, “Fact v. Fiction”